by Shirley Seale

Mary Bligh, who has been described as the sauciest, daintiest and most determined little spitfire ever to preside at Government House, was an independent and strong willed woman. Her association with Riverstone began on the occasion of her marriage to Maurice O’Connell, Lieutenant Governor of New South Wales, when Governor Macquarie made a grant to him of 2500 acres of land, which O’Connell named Riverston after his birthplace in Ireland. Much has been written about O’Connell’s career, but it is Mary whose life had all the drama of a current television soap opera!

The Early Years

Mary Bligh was born to Elizabeth and William Bligh in London, early in 1783. She was the second daughter, her sister Harriet having preceded her. She was to have five sisters in all, for she was followed by Betsy, twins Frances and Jane, and Ann. The Blighs also had twin sons, who died when only one day old.

The only information we have of Mary as a child comes from a letter from her father to John Bond, who was married to his half-sister, Catherine, on 7th April, 1783:

I found Mrs Bligh very well, but the child, from her severe teething illness, suffering a great deal and indeed to add to all, a general breaking out over all her body and limbs, which most certainly was the itch. However, I am happy to say that from partial rubbings and her teething illness going off, she is survived to a pretty child.

During her early childhood, the family lived at Belle Vue, Hampden; Norse Moor Place, Lambeth; Durham Place, Lambeth; but after 1789 appear to have settled at 3 Lambert Place, London. They seem to have been a close family, despite Bligh’s problems with his career, as he wrote to, and about, them often. On August 19th, 1789, as he was in Timor waiting to return to London after the calamitous events of the mutiny on the Bounty, he wrote to his wife: Know then, My own dear Betsy, that I have lost the Bounty, and tells her at great length of the troubles he endured, but, at what was surely the worst time of his life, he remembers his girls. Give my blessing to my Dear Harriet, my Dear Mary, my Dear Betsy and to my Dear little stranger and tell them I shall be home soon.

Coming to Australia

It was Sir Joseph Banks who recommended Bligh for the position of Governor of New South Wales, as a firm disciplinarian, much needed in the colony. Bligh was reluctant at first as Mrs Bligh, being a very poor sailor, refused to go on another sea trip. Furthermore, he felt that the salary of one thousand pounds, ($2000), which had been paid to all previous Governors, was insufficient for him to live well and put some aside for later. It was agreed that his salary would be doubled and Bligh was appointed Governor and, in addition, Commander-in-Chief, on full pay, of all British ships in the N.S.W. station. Accordingly he was able to request his son-in-law, John Putland, be appointed as his naval Lieutenant and this meant that he could be accompanied by his daughter Mary, now Mary Putland, who would act as Governor’s Lady.

John Putland at this time, was a half pay Lieutenant, already with early signs of T.B., but Bligh proudly asserted that Putland was the first rating to be elevated to the rank of Lieutenant by Lord Nelson himself after the Battle of the Nile.

Bligh assured his wife that their separation would not last longer than five years and Mrs Bligh, who was a noted natural historian with a special interest in seashells, seemed contented to remain in England and wait. Bligh, John and Mary Putland embarked on the ship Lady Madeleine Sinclair and Mary wrote to her family: In this ship there are female as well as male convicts, among the latter is a clergyman named Newishman, a man of very good family. His wife is with him, they say a very genteel woman. Mary relieved the tedium of the long sea voyage by writing frequently to her mother and sisters, so we know that the very next day Bligh planned to visit Fortune another convict ship.

She writes again that at 10 a.m. Papa went on board the Alexander to see the state of the ship and convicts. They, poor unfortunate creatures, were delighted to see him. Bligh promised them that if their behaviour was good he would see if he could ameliorate their conditions. Also in the convoy was the Elizabeth, a whaler whose captain had a grant of land at Port Jackson, and the Porpoise.

They had not been at sea long when Lt. Putland was transferred to the Porpoise, while Mary stayed with her father. Soon after, the first portent of arguments to come occurred when Bligh, who considered himself to be totally in charge of the whole operation, ordered his ship to change course. This angered Captain Short on Porpoise, who had been entrusted with command of the ships at sea. He signalled Bligh to return to course, and when he took no notice, Putland was ordered to fire on the ship containing his wife and father-in-law. He refused to do so and the confrontation was ultimately defused when Bligh brought his ship back into line.

During the voyage Mary wrote to her family: Papa has purchased sapphires, emeralds and amethysts for Mamma and all of you – Mamma’s to be the handsomest of course.

The Arrival in Sydney

The party landed in Sydney on 8th August, 1806. The Sydney Gazette recorded, We are extremely happy to state that Governor King’s successor is accompanied by his amiable daughter, Mrs Putland, a circumstance which conveys the greatest pleasure and cannot fail being attended with the most beneficial consequences. Governor King almost immediately made Bligh a grant of 1000 acres on the Hawkesbury which he later turned into a model farm with Andrew Thompson as Bailiff, and 600 acres at St Marys for John and Mary Putland. Bligh returned the gesture with a grant to Mrs King, which she named Thanks.

The Blighs soon made their presence felt in Sydney Town. Bligh sent home to England some Rosehill parrots, but regretted that the emu egg, presumably being carved, was not finished, and Mary sent home feathers for her mother and sisters. Her sister Elizabeth wrote her thanks and said she thought them the most elegant of the kind I ever saw. She had been told they were from an egrette of the bittern tribe and told Mary that her mother had distributed them as favours to friends and people who had done them past kindnesses.

The gift giving was not all one way for Mrs Bligh sent Mary three pairs of silk stockings, six pairs of gloves and four pairs of shoes, besides some music, and Mary in a letter from Government House to her sister tells how excited she was by the receipt of a new gown, which was altogether different and superior to anything of the kind which has been seen in this country. Perhaps it was this gown which she wore to services at St Philip’s church one famous Sunday. Denton Prout describes the scene in the book, Petticoat Pioneers (page 41): the gown, a modish one, suited her to perfection, but it was so thin as to be almost transparent in the strong Australian light. It gave some of the soldiers sitting in the church such a lesson in the complexities of feminine wearing apparel that their minds were taken from the study of their prayer books. Mary was not wearing petticoats, and the long lacy pantaloons she wore underneath were visible to all. A series of lascivious chuckles ran through the church. Mary looked haughtily around to see what was causing the amusement. Then, realising that she was responsible, she did the only thing a woman of her upbringing could do in the circumstances. She fainted. Bligh, once his daughter had been carried prostrate from the church, angrily demanded explanations and apologies from the soldiers, thus further exacerbating the ill feelings that were mounting towards him as he introduced harsh methods to restore order in the colony.

The Beginning of Trouble

On the 10th October, 1807, Mary wrote to her mother, Papa is quite well, but dreadfully harassed by business and the troublesome set of people he has to deal with. In general he gives great satisfaction, but there are a few that we suspect wish to oppose him….Mr Macarthur is one of the party, and the others are the military officers, but they are all invited to the house and treated with the same politeness as usual.

Macarthur was indeed stirring up trouble, although in the previous January he had written to a friend, Our new Governor, Bligh, is a Cornish man by birth. Mrs Putland, who accompanied him is a very accomplished person. This was before he realised that Bligh would seek to prevent him trafficking in rum, which had been a perquisite of the N.S.W. Corps, and he was now recruiting other military officers to his side against the new Governor. Bligh, however, remained popular with many settlers, especially those of the Hawkesbury region, whom he had helped fairly and generously after a disastrous flood.

There is little mention of John Putland at all and Mary’s first loyalty seemed to belong to her father. On 24th August, 1806, Bligh had appointed Putland his aid de camp(sic), and a magistrate throughout the territory and its dependencies and in January, 1807, Putland was appointed Commander of the Porpoise in the absence of Captain Short, who had gone to England on the Buffalo. Putland’s health must have been deteriorating steadily, however, and in November of the same year Bligh had written to Joseph Banks of John’s grave condition, and the traumatic effect it had on Mary, for they were inestimable to me, so you will feel for the distress we are in besides my apprehension for my daughter’s health. She has been a treasure to the few gentlewomen here and to the dignity of Government House. Only 16 months after their arrival in Sydney, John Putland died of tuberculosis on 4th January, 1808, and was buried in the grounds of Government House. Bligh had been very fond of his son-in-law and was said to be deeply affected by his death, perhaps to the extent of clouding his judgement during the difficult time coming.

The Rum Rebellion

Putland had only been dead for two weeks. Mary, a widow at twenty six, and her father were still in deep mourning. The officers of the N.S.W. Corp, goaded by Macarthur, decided the time had come to depose the Governor for his stringent policies on the importation of stills and on their lucrative monopoly on trading in rum. Although John Macarthur had signed an address of welcome to Bligh on behalf of the free citizens of the colony on Bligh’s arrival in August, 1806, his mind was now changed. Matters came to a head after Bligh had decided two court cases against Macarthur, one regarding the prohibited importation of stills. Macarthur moved to Sydney to be on hand to engineer the revolt. At last, after an abortive third trial, on 26th January, 1808, Macarthur and nine of his close associates petitioned Lieutenant Governor Johnstone to remove Bligh from office and he agreed.

So, on the 20th Anniversary of the founding of the colony, the Corps was ordered to march on Government House. Soldiers with fixed bayonets over-ran the grounds of the residence, pushing aside Mary and trampling on the grave of her newly buried husband. Johnstone, writing to Captain John Piper, the Commandant at Norfolk Island on 2nd February, (Piper was collecting shells for Mrs Bligh at this time), informed him of the event and assured him that not a single instance of disorder or irregularity took place, but that Bligh was nowhere to be found, but after a long and careful search he was at last discovered in a situation too disgraceful to be mentioned. A political cartoon of the day showed Bligh being pulled from under the bed, the inference being that he was hiding, but according to Merchant Campbell, who was dining with Bligh that night, the Governor was attempting to hide secret papers Campbell writes, We had just drank about two glasses of wine after dinner, when we understood that Mr Macarthur was liberated from gaol. The Governor almost immediately rose from the table and went upstairs to put on his uniform and I heard him call to his orderly to have his horses ready. I accompanied him upstairs and saw him open his bureau or trunk and take out a number of papers, when Mr Gore entered and delivered him Major Johnstone’s order for the liberation of Mr Macarthur. I had scarcely read that order when I heard Mrs Putland’s screams, upon which I immediately ran downstairs to the gate at the entrance to Government House where I found her endeavouring to prevent Mr Bell, who commanded the main guard, from opening the gate. I saw the gate opened and a party of soldiers and officers marched in. (Campbell was friends with Bligh and often visited him. He had given Mary a shawl in the way of a friendly present.)

Mary alone attempted to resist by force the intrusion of these soldiers, laying about her with a parasol to fend off the men trying to get through the bedroom door. One eyewitness reported: The fortitude evinced by Mrs Putland on this truly trying occasion merits particular notice, for regardless of her own safety and forgetful of the timidity peculiar to her sex, her extreme anxiety to preserve the life of her beloved father prevailed over every consideration and with uncommon intrepidity she opposed a body of soldiers who, with fixed bayonets and loaded firelocks, were proceeding in hostile array to invade the peaceful and defenceless mansion of her parent, her friend, her protector, and as she then believed, to deprive him of his life. She dared the traitors to stab her to the heart but to spare the life of her father. The soldiers themselves, appalled by the greatness of her spirit, hesitated how to act and that principle of esteem and respect which is inherent in the breast of every man who sees an amiable woman in distress, and is not himself a most consummate villain, deterred them from offering any violence to her.

It was Lieutenant Minchin, later of Minchinbury Estate, who physically removed Bligh from his bedroom and escorted him downstairs to hear formally of his deposition.

It is unfortunate that due to a lack of paper, no newspaper account of these events is available, as the Sydney Gazette was not published between August 1807 and May 1808. But we do know that Macarthur, hero of the day, paraded around the streets where bonfires blazed and riotous behaviour occurred.

Arrest and Detention

There was a lull for about a year, while Bligh and Mary were under house arrest, and little is known about the lives of the pair during this time at Government House, but suddenly they were returned to the spotlight when the rebels went to Bligh and demanded that he return to England on the Admiral Gambier. This he refused to do. Although he was no longer Governor, Bligh could not have his naval powers taken from him. Bligh still had command of the Porpoise, although he was not allowed to go on board. Johnstone wanted to use the Porpoise and he ordered Bligh to give up command of the ship or be confined to barracks. Bligh again refused. Bligh wrote, I went to my daughter and reconciling our feelings to our reputation, we parted.

Johnstone put Bligh into a one horse chaise and drove with him. Now Mary comes back into the limelight. Once again showing great courage and spirit, Mary pursued the carriage on foot and caught up with it, much to the astonishment and entertainment and indeed admiration of the populace. The picture is best described in Bligh’s own words.

He had only drove me 200 yards, when I found my beloved child, under a vertical sun, rushing after me, having passed Captain Abbott, who told her she need not go for they would not let her in. Bligh, who was riding in front, was almost at bursting point at the sight of his amiable daughter fainting and sinking under the accumulation of such unmerited wrongs and insults wantonly heaped on her beloved and respected parent.

Mary persisted, running along the street in the heat of a summer’s day, and arrived at the Barracks when the carriage did. Bligh continues and seizing hold of my arm, we walked into it, passing Lieutenant Colonel Foveaux, who came to direct Major Johnstone where I was to be confined. This happened to be a subaltern’s barrack. It consisted of two rooms with a bed in one and a sofa in the other. I had just got her to the sofa when distress of mind, and the great heat she had passed through overcame her.

Although her entry was voluntary, Mary was warned she would have to share her father’s confinement. Soldiers were sent for some clothes and necessary articles for her and she used the bed while Bligh took the sofa. Soldiers’ women waited on them, although her maid was allowed in to share the two hot little rooms some days later and three armed sentries kept guard over them.

The Tasmanian Excursion

Paterson was anxious to get the Blighs out of the colony and after seven days strict confinement, they came to an agreement. Bligh was to go with his daughter on board the Porpoise on 20th January and sail for England without touching any part of the territory, being allowed to return to Government House for the few days remaining. Johnstone said Bligh could take with him anyone he needed as a witness in the enquiry which would be held. However, Johnstone refused to release one of these people, so as soon as Mary and Bligh set sail, Bligh repudiated his promise, feeling that he was no longer bound to its terms, and sailed to the Derwent River in Tasmania and remained there.

Poor Mary suffered, for she was a bad sailor, so on arrival in Hobart Bligh went ashore to Government House, where David Collins was ensconced. Bligh described it as a miserable shell of three rooms and preferred to return each night and sleep on the ship. However, he left Mary ashore as Collins’ house guest. The two men finally had a fierce argument over the removal of a sentry from Government House, so Bligh removed Mary from the house and took her back to the ship. He insisted that Collins had insulted Mary by parading around, arm in arm, with his mistress, Margaret Eddington who was pregnant at the time.

Bligh removed the Porpoise down river to establish a blockade to stop all shipping movements in and out of Hobart. Collins ordered all people to have nothing to do with the ship and said he would fire on any boat going ashore from her. This made obtaining food very difficult for Bligh and Mary and he was forced to demand food from the ships he was trying to stop. They stayed there for six months until he heard in December 1809, that Macquarie was due from England, so Bligh set sail again for Sydney. Macquarie had his ship sail close to Hobart in the hope of meeting Bligh, but thick fog kept the ships from each other.

Return to Sydney

Bligh arrived in Sydney on 17th January, 1810, and he and Mary were welcomed by Governor Macquarie and invited to stay at Government House. Macquarie wrote in his journal, Commodore Bligh, accompanied by his daughter, Mrs Putland, came on shore and I invited them to dinner, but they declined. He did not know that they had already been introduced to his Lieutenant Governor, Maurice O’Connell, who had issued an invitation for them to dine with him and been accepted. Reports vary on whether Macquarie provided the Blighs with a house to live in, or whether Bligh himself rented the house in Bridge Street, close by the Tank Stream at ten pounds a month, but either way Bligh insisted on being provided with a protective guard from Macquarie’s 73rd Regiment, the Second Black Watch. The Hindostan was being prepared for his return to England, and Bligh insisted on being saluted each time he went aboard or came off the vessel, often as many as six times a day.

The Betrothal

At the time that Mary Bligh Putland met Maurice O’Connell, she was 27 years old and he was a 42 year old bachelor. Unbeknown to Bligh, who was busy preparing to leave the colony, Mary and Maurice were forming a serious attachment and when Bligh left on St Patrick’s Day to tour the Hawkesbury and see his farms again, Mary and O’Connell decided on a match.

Maurice Charles O’Connell was born in Riverston in County Kerry, Ireland in 1768. He was educated mainly in France where he studied for the priesthood. He then fought in the Irish Brigade with the French Army. Transferred to the British Army, he had a good military record before he joined Macquarie’s 73rd Regiment and came to N.S.W. in command of the Regiment and as Lieutenant Governor. Before the Hindostan was ready to sail, he had proposed to Mary and been accepted. Mary, however, kept the betrothal secret and actually packed her belongings and boarded the ship on 5th May. O’Connell then gave a grand dinner party at which he announced their marriage plans. Macquarie, who was aware of the disruption the presence of the Blighs caused in the colony, had been anxious to see them go, but was prepared to put a good face on it.

We have an interesting pen portrait of Mary at this time written by Ellis Bent, the new Judge Advocate who had arrived with Macquarie. Very small, nice little figure, rather pretty, but conceited and extremely affected and proud. God knows of what! Extremely violent and passionate, so much as now and then to fling a plate or candlestick at her father’s head ……..everything is studied about her, her walk, her talking, everything …… and you have to observe her mode of sitting down ……..dressed with some taste, very thinly, and to compensate for the want of petticoats wears breeches or rather, trowsers. He called the marriage a cursed match and continued, she is very clever and plays remarkably well on the pianoforte. I regret extremely this marriage, for in the first place I dislike her, and in the next place it crushed the hopes I had formed of seeing comparative harmony restored to the colony. He was one of the few who recognised what was going to happen and he wrote to his brother: I immediately divined the fact and now know that the Colonel is going to marry Mrs Putland, who has prepared all her accommodations aboard the Hindostan. He felt the marriage would encourage the split in the colony and make the place very unpleasant.

The Marriage

Macquarie ignored the rumour that Mary’s motive in marrying O’Connell was to settle in an important social position from which she could snipe at her father’s enemies. She brought to the marriage a large dowry in the form of her previous land grant and cattle, and Macquarie gave O’Connell a grant of 2500 acres at Riverstone as a wedding gift. The grant was made on the 7th May and the wedding took place on the 8th. Governor and Mrs Macquarie gave them a dinner at Government House, the ballroom being decorated with flowers and with festoons encircling a device showing the initials of the happy couple. The event culminated with a display of fireworks. This sumptuous ball had originally been planned to farewell the Blighs and was quickly adapted to suit both occasions. The wedding ceremony was conducted by Samuel Marsden and took place at Government House. Bligh gave the bride away. The Sydney Gazette gave no details of the wedding, just a brief official notice, but it did publish a very fulsome poem to celebrate the event.

Strike! Loudly strike the lyric string;

To Bridal Love devote the song;

Let every muse a garland bring

And Joy the festive note prolong!

To P……..d, amiable and fair

Soft as her manners pour the warbled lay;-

Another bolder strain prepare

For brave O’C………l on his nuptial day!

In Australia’s genial clime proclaim

Their love and valour blend their spotless flame

And wreaths of sweetest flowers prepare

For lovely P……..d’s flowing hair.

The poem ended with the line

And children’ children crown their virtuous love!

For some reason it was deemed improper to have printed their names in the poem, and it was left to the readers to fill in the blank spaces!

Bligh had not at first viewed the match with favour and he was fearful about what his wife would think of it, so he delayed informing his family until he reached Rio, when he wrote this letter:

“Hindostan”, 11th August 1810

in Rio de Janiero.

My dearest love,

Happily I am thus far advanced to meet you and my dear children. I am now well, as is our dear Mary, altho I have suffered beyond what at present I can describe to you. Providence has ordained certain things which we cannot account for; so it has happened with us. My perfect reliance that everything which occurs is for the best is my great consolation. In the highest feelings of comfort and pride of bringing her to England, altho I thought she could be under no guidance but my own – my heart devoted to her – in the midst of most parental affections and conflicting passions of adoration for so good and admired a child, I at the last found what I had least expected – Lt. Col. O’Connell commanding the 73rd Regiment had, unknown to me, won her affections. Nothing can exceed the esteem and high character he has. He is likewise Lt. Gov. of the territory – a few days before I sailed when everything was prepared for her reception, and we had even embarked, he then opened the circumstance to me – I gave him a flat denial for I could not believe it – I retired with her, when I found she had approved of his addresses and given her word to him. What will you not, my Dear Betsy, feel for my situation at the time, when you know that nothing I could say had any effect; at last overwhelmed with a loss I could not retrieve, I had only to make the best of it. My consent could only be extorted, for it was not a free gift. However, on many proofs of the Honour, Goodness and high character of Colonel O’Connell and his good sense, which had passed under my own trial I did, like having no alternative, consent to her marriage and gave her away at the ceremony consummated at Government House, under the most public tokens of honour and respect and veneration, the whole colony, except a few malcontents, considering it the finest blessing ever bestowed upon them – every creature devoted to her service by her excellence, with respect and adoration…………they remain persons of the utmost importance to the welfare of the colony and the admiration and respect of Gov. and Mrs Macquarie, who did the honours of the ceremony at Government House with an extraordinary degree of pleasure and even adulation.

Bligh must have been very hurt by Mary’s duplicity, when he would have felt every confidence in her loyalty to him after all they had been through together. That he had been totally ignorant of the situation is shown in a previous letter he wrote home: The “Hindostan”, being large and commodious, my Dear Mary will feel more comfortable situated and particularly as she will have pleasanter society than in the “Porpoise”, a ship by no means agreeable to her.

So they were obviously expecting Mary to return home to England with her father, and what Mrs Bligh thought of this sudden change of plan is not recorded. Bligh did however take with him a letter from Mary to her mother, although we do not know the contents, and he concludes his letter from Rio by assuring his wife, Thus, my dearest love, when I thought nothing could have induced our dear child to have quitted me, I have left her behind in the finest climate in the world. To have taken her into the tempestuous voyage I have now formed, I believe would have caused her death. Everything Honourable and affectionate has been performed by Col. O’Connell which I soon hope to communicate to you.

Bligh left for England on 12th May, having given Mary bills of 140 pounds to settle her accounts before her marriage.

Mary and Maurice O’Connell lived in barracks in Wynyard Square until 1812 when O’Connell rented Vaucluse Estate at Vaucluse until 1814. Presumably the O’Connells, Mary, sometimes called a spitfire, and the amiable Maurice, settled down to married life. When Macquarie set off on a tour of inspection,

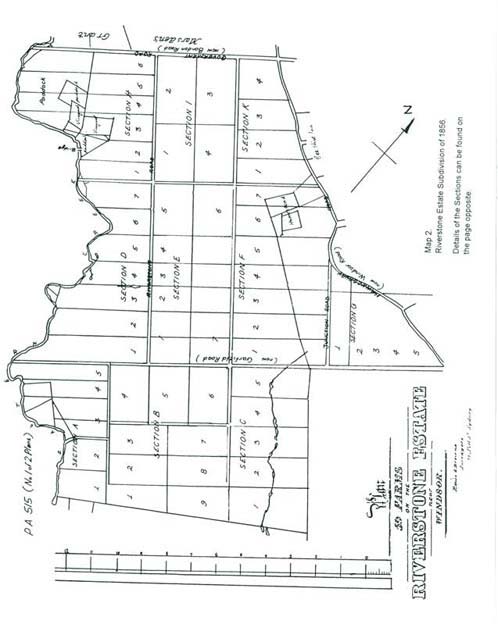

he wrote in his diary that on Wednesday, 28th November, 1810 he, with Mrs Macquarie, Mr Gregory Blaxland and others crossed South Creek and travelled along the right bank to Mr Marsden’s farm, then re-crossed the creek to Mrs O’Connell’s farm at Frogmore. On Saturday, 1st December Macquarie leaves the Kurry-Jung Hill named by the late Mr Thompson, Mount Maurice out of compliment to Lt. Col. O’Connell and on the following Saturday, 8th December, he writes, At 9 o’clock this morning, immediately after breakfast, Mrs M. and myself set out in the carriage from Windsor to Parramatta, accompanied by the gentlemen in our family and Mr Hassall. We halted for about a quarter of an hour at Lt. Col. O’Connell’s farm of Riverston (granted to him by me on his marriage) distant about 6 miles from Windsor on the high road to Parramatta, examined his dairy and stock yards and then pursued our journey. The O’Connells had made some improvements to their grant in just seven months. Mary and Maurice’s Riverston Farm homestead, (the E was not added to the name until an error was made in the spelling when the railway was built), was located at the junction of Crown and Junction streets, close to Windsor Road.

By 1811, Mary was pregnant, and on King’s Birthday of that year, 72 persons, including five ladies, one of them Mrs O’Connell, were entertained at dinner at Government House. There were constant wagers, it seems, upon when Bligh’s turbulent daughter, who, it was reported, had worn a fevered and anxious expression throughout the year, would add to the O’Connell clan. In fact her son Maurice Charles Junior, was born in January, 1812. Governor Macquarie was his godfather. By 1812 also, Mary’s land grant at St Marys of 600 acres had been swelled by 1055 acres granted by Macquarie to her. She had stocked the land and in that year bought from the government 8 cows, 9 oxen and 25 sheep, for which she paid a total of £386. ($772)

Although from these facts we would assume that Macquarie really liked and approved of the O’Connells, he realised that Mary was still the reason for a lot of discontent in the colony. In 1813 he wrote to Lord Bathurst and asked for a withdrawal of the 73rd Regiment and its Commanding Officer, for the peace of the colony. He wrote, Mrs O’Connell, naturally enough, has imbibed strong feelings of resentment and hatred against all those persons and their families who were in the least inimical to her father’s government. Lt. Col. O’Connell allows himself to be a good deal influenced by his wife’s strong-rooted prejudice against the old inhabitants, although he asserted, Lt. Col. O’Connell is naturally a well disposed man……..it would most assuredly greatly improve the harmony of the country if the whole of the officers and men of the 73rd Regiment were removed from it. As this was Macquarie’s own regiment, he must have had very strong feelings indeed that Mary had to go.

Accordingly, O’Connell was transferred with his regiment to Ceylon on 28th March. Macquarie held a farewell dinner for them and a welcome dinner for the new Lt. Governor, George Molle. They were thus present at Government House on the evening when Governor Macquarie’s son, Lachlan, was born. Macquarie wrote that there were 38 persons present at the large dinner, including Lt. Governor O’Connell and his lady, who slept at Government House, presumable before boarding the General Hewitt for Ceylon. The party broke up about half an hour before Mrs Macquarie gave birth. She had not attended the dinner as she had been in labour all afternoon. The O’Connells were aroused by a loud knocking at their door to announce the happy news.

The Years Away

So the O’Connells left Sydney, although as it transpired, not for good. Mary and Maurice had more children, Richard O’Connell, Charles Phillip, William Bligh, Robert Browning, Mary Nino Godfrey and Elizabeth.

Robert Browning, who had been born in December, 1817, died in Ceylon when he was only 14 months old, and there is a very sad story from the Gazette, 14th February, 1819.

Mrs O’Connell must have suffered severely from the powerful trial to her maternal affections. Her little boy was taken ill in their passage at the beginning of a gale wind that lasted some days, during which she was herself much indisposed, and both were deprived of all professional assistance as the only medical gentleman on board the transports, was unfortunately on another ship. On landing, some hope was entertained but it was soon dashed away and in a few days the afflicted parents were doomed to see the death of their boy, whose improved health and bloom they had at the commencement of the voyage contemplated with such delight.

Mary Nino Godfrey also died young, in Athlone, Ireland on 19th February, 1825. She had been born in 1823.

After leaving Ceylon, O’Connell retired on half pay to England where he was promoted to Major General in 1830. In 1834 the O’Connells were posted to Malta and he was knighted in 1835.

The Return to Australia

In 1834 the O’Connells were returned to Australia in the Fairlie, Maurice having been appointed to command the forces in N.S.W. Their son Maurice who was a captain in the 73rd Regiment, came with his father as his military secretary.

It was not long before Mary’s presence was felt by the then Governor, Gipps. In August, 1839, he reported to the Colonial Office that Sir Maurice O’Connell was claiming on behalf of Bligh’s heiresses, 105 acres at Parramatta worth about £40,000, ($80,000), and including the sites of the Female Factory, the gaol, the King’s School, the Roman Catholic church and chapel and many houses. His attorney had sent notices of ejection to all occupiers of the land. Gipps directed attention to the extreme delicacy of the position in which this business has placed me, since O’Connell was the senior member of the Executive Council and if the Governor were to die, would succeed to the position. At length, in February, 1841, a settlement was reached whereby the heiresses surrendered their claim to the Parramatta land but their titles to other grants were confirmed. One of these, Camperdown, the site of the present suburb, was later sold for £25,000, ($50,000), a huge sum for those days.

Mary and Maurice resided in a mansion called Tarmons at Woolloomooloo which now forms part of St Vincent’s Hospital. They put their Riverston property up for sale in 1845. They entertained lavishly at Tarmons and one dinner is described by a guest, Adjutant General Mundy, in 1846.

I dined this day, 29th June, with my respected chief Sir Maurice O’Connell, at his beautiful villa, Tarmons ………there were brisk coal fires burning in both dining and living room and ……..the general appliances of the household, the dress of the guests and servants were entirely as they could have been in London. The family likeness of an Australian and Old Country dinner party became less striking when I found myself sipping doubtfully, then swallowing with relish, a plate of wallabi(sic) tail soup, followed by a slice of boiled schnapper with oyster sauce. A roast of kangaroo venison helped to convince me……..a delicate wing of the wonga-wonga pigeon and sauce, with a dessert of plantains and loquats, guavas and some oranges, pomegranates and cherimoyas landed my decision at length firmly in the Antipodes.

Mary found time to serve on many public committees including a Ladies Committee set up to support Caroline Chisholm’s work with migrant women, on which she served with Lady Gipps.

O’Connell became Acting Governor on 12th July, 1846, after Governor Gipps left for England and until Governor Fitzroy arrived. So the wheel turned full circle and Mary was once again the Governor’s Lady until December 1847. Maurice O’Connell died at the age of eighty in his home on the very day he was to return to England, 5th May, 1848. He was accorded a full military funeral at St James Church. The Sydney Morning Herald carried a full description of the funeral procession, which was attended by a huge crowd, and listed the mourners. They also ran a long obituary which told the events of his busy life, but at no time was any mention made of Mary!

Mary did return to England where she died at the residence of her son-in-law, Colonel Somerset, at Beaufort Buildings, Gloucester, on 10th December, 1864, aged 81.

Her son, Sir Maurice O’Connell Junior, who made a very distinguished career in the Queensland Government, died in 1879 and William Bligh O’Connell died in 1896, while her daughter Elizabeth died in 1892. A grandson, Mr W.B. O’Connell was Minister for Lands in Queensland and died in 1901, leaving 9 children. A great-grandson was prominent in Sydney in the 1930s so the O’Connell influence in Australia remained strong long after Mary had departed.

Mary Bligh Putland O’Connell was a strong woman who attracted strong opinions both for and against almost everything she did. Yet she was a dutiful daughter, a loving wife and mother, who stood up against the iniquities she felt had been unjustly visited on her family. In the days when men ruled the world, Mary was there fighting for the rights of women and showing the strength there is in us all.