by Ron Mason 28th June 2013

Laurie Hession [1923-2004] was a collector. He collected stamps, coins, bottles, farming implements, household appliances and lots of other things that some people would dismiss as junk. Laurie was also a local historian with a great enthusiasm for the heritage of Nelson, Box Hill and Riverstone. Not surprisingly, his collection included many items that are important in helping us to understand the history and way of life that characterised these small farming communities – an understanding that will only become more important as these communities are displaced by Sydney’s urban growth.

Earlier this year, Laurie’s family invited the Riverstone and District Historical Society to view his collection and to nominate items that the Society felt were appropriate for inclusion in the Riverstone Museum collection. As a consequence the family generously donated a number of significant items to the museum.

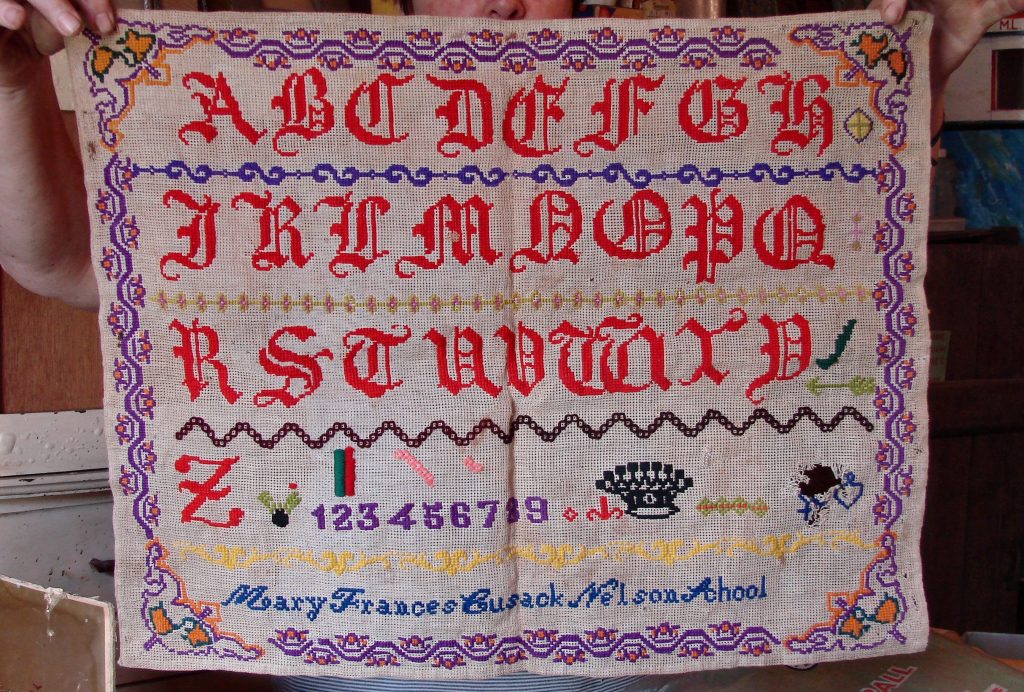

This sampler is an important addition to the Museum’s collection because it is a rare and well-preserved example of a 19th century, school-girl’s needlework. It is also important because it is one of only two known existent artefacts associated with the Nelson Denominational School, which operated from 1866 to 1883 and was most probably the earliest school in the district. Finally, it is important because of its associations with two of the district’s pioneering families – the Cusack and Mason families.

LEARNING NEEDLEWORK SKILLS

In the days before the ready availability of cheap, mass-produced clothes and when hand embroidered and crochet doilies, milk jug covers, tablecloths, cushion covers and other pieces of needle craft were found in most Australian homes, sewing and embroidery were considered to be essential skills for all schoolgirls. Indeed the revised “Timetable for National Schools” introduced in 1851 required girls to devote one hour each day to needlework 1 . This requirement applied to all NSW schools regardless of whether the school was a rough slab and bark building accommodating a handful of farmers’ children or a prestigious city school.

To demonstrate that they had satisfied the requirements of the syllabus girls were expected to produce an embroidered sampler 2. These samplers served several purposes. They were a record of the stitches and patterns learned as well as a demonstration of the student’s needlework skills. They were also a means of teaching the alphabet, numbers and even multiplication tables.

Typically school samplers were of a kind known as band or marking samplers. These were worked in bands or rows usually with a repeat border design and commonly incorporating the alphabet, numbers, motifs and sometimes a verse or quotation 3. It was also usual to include the student’s name, their school and the date on which the sampler was produced.

These samplers could be quite elaborate and finely worked and many became cherished family keepsakes that were handed down from generation to generation. The sampler, now in the Riverstone Museum is one such example.

MARY FRANCES CUSACK

So who was Mary Frances Cusack? The short answer is that she was the Nelson Denominational School master’s daughter and her mother was the sewing teacher.

Mary’s father James Cusack arrived in Sydney as an assisted Irish immigrant on board the bounty ship Fortune in 1853. He was 29 years of age, single, and although he identified himself as a farm labourer, he was able to read and write – skills which were sufficient for him to be accepted by the Denominational School Board as a pupil-teacher and, after seven months training, as the teacher at Cattai Creek Denominational School 4.

While at Cattai, James Cusack met and subsequently married another Irish immigrant, Rose Brady. Rose had travelled to Australia, with her two sisters and two brothers, in 1854 to join another brother, James, who had arrived some time earlier. James subsequently acquired land on the banks of Cattai Creek not far from the Cattai School and so the Brady family and James Cusack became neighbours. In more recent times, the Brady farm became a popular picnic spot known as “The Willows Picnic Park”.

In 1858 James and Rose married and set up home in the slab and bark residence provided for the teacher. They had six children, including Mary, and all were born during their time at Cattai.

The following photograph was probably taken during the early 1880s before her marriage to Samuel Mason Jnr in 1886. It was copied from an original Tintype (also known as Ferrotype) that was in the possession of her granddaughter, Ronnie Huxley nee Mason. The invention of the Tintype in 1854 brought the reality of photography closer to the mass population.

THE NELSON DENOMINATIONAL SCHOOL

Eight years later a new school was built at Nelson and the Denominational School Board approved the transfer of James Cusack and his stipend from Cattai Creek 5. A history of the Nelson school was published in the Society’s 2005 Journal.

The new school was located in Old Pitt Town Road on 3035 square metres of land purchased from Samuel Henry Terry. The school had a single class room and an attached teacher’s residence which had four large rooms 6. It was built of “Posts and slabs, [with] 2 stone chimneys, [and a] roof [of] shingle.” 7 It also had a verandah along its long side and a detached slab kitchen with a bark roof.

One newspaper report credited Samuel Mason senior with having built the school and although it was located only about a hundred metres from his farm house, “Ironbark Park”, it is more likely that the whole of the Nelson community contributed to its development. Certainly all of the local children attended it, irrespective of their denomination.

Mary Cusack, who was just two years old when the family moved into the Nelson schoolhouse, was to spend the next seventeen years living there and it was during this time that she embroidered her sampler – almost certainly under the guidance of her mother. It was also during this time that she would have met a fellow student – Samuel Mason junior, whom she was to marry some years later.

In 1880 the Public Instruction Act took effect – severing the tie between the church and state school systems and withdrawing state aid from church schools. As a consequence many church schools were transferred to the state. The Nelson School was no exception and late in 1882 Dr. Sheehy, parish priest for Windsor, advised the Department of Public Instruction that the church was prepared to lease its Nelson school to the Department provided James Cusack was retained as its teacher. The Department agreed and a 2 year lease at an annual rental of £12 was signed on the 1st January 1883 9.

Six months later James Cusack retired and as a consequence the family had to vacate the school master’s residence. Where they lived for next few years is not known although when Mary married in 1886 she gave her place of residence as Nelson.

MARY CUSACK BECOMES MARY MASON

In 1886 Mary Frances Cusack married Samuel Joseph Mason. Samuel was the second son of Samuel Mason and Sarah Hession and was the third generation of the family to bear the name Samuel.

About twelve months before Mary and Samuel married, Samuel’s father purchased a saw mill at Riverstone and throughout the early years of his married life Samuel junior, as he was usually identified, worked as the benchman at his father’s mill and in later years took full control of it.

On 25 July 1891 James Cusack purchased this land in Sydney Street, Riverstone. This photo was taken in 1930 by family friends who had emigrated from Ireland with James, W.W. Norquay.

The car, believed to be a 1928 Buick belonged to the Norquay family.

The Cusack family lived in the house until about 1935 when it was demolished. (Copied from a photo from Brian Mason.)

It was also during this time that Samuel and Mary purchased two blocks of land in Crown Road, Riverstone on which they built a modest slab cottage. Twelve months later Mary’s father purchased a neighbouring property in Sydney Street –and so Mary’s parents, her unmarried siblings, Will, Sarah [Sadie] and Kate, and her maiden Aunt Theresa Brady were living just a short walk away. Both families expanded their land holdings over the years and both continued to live there until there were no longer any surviving members.

On 8th August 1890 Samuel Mason purchased two blocks of land in Crown Road and built this modest, white washed slab cottage. The photo shows the rear of the cottage. To the left is their 2nd house.

The man on the left is Vincent Mason (teacher Annagrove school) and his brother Joe. The boy is one of Joe’s sons. (Original photo from Ronnie Huxley.)

These would have been goods days for Sam and Mary. Their family was expanding and Sam had steady employment at the mill. However, by 1899 the Mason mill had ceased operations and Sam became the benchman at Jim Ouvrier’s Riverstone mill. It was then that he suffered a serious accident that was to end his days as a sawyer and to cause great hardship for the family. The local newspaper reported that while he was working at the bench of Ouvrier’s mill “Three fingers and the thumb of the left hand were severed, part of the hand also being cut off.” 10

For a comparatively young man with a wife and six young children, the youngest of whom was only four weeks old, this was a devastating event. He was unable to work and there were no such things as workers’ compensation or unemployment or disability payments. However, the people of Riverstone rallied to their support. The press reported that “The Riverstone cricketers have taken it upon themselves to assist Mr. Sam Mason in his distress, and are organising a concert … Riverstone is certainly one of the best hearted and most charitable communities we know.” 11 Despite this help, their life became a struggle. Mary’s only daughter, Cass Mason, recalled many years later that the family “was very poor, she wasn’t sure how they survived – although things got better as the family grew up and went to work”. 12

MARY’S CHILDREN

Mary and Sam had eight children – seven boys and a daughter. Four of the boys: Joe, Austin, Ambrose and Vincent, followed in their grandfather’s footsteps by becoming school teachers – all at country hamlets. Their fifth son, Frank, became the long-serving Town Clerk of Windsor while Jim, their youngest, remained at Crown Road where he became a poultry farmer. However, Jim can claim some connection with schooling as the first, purpose-built school building to be erected at St John’s School Riverstone is named the “James Mason Memorial School” in his honour.

Cass, who was the longest surviving member of the family, was sent to secretarial school in Sydney. In later life she “wondered how her parents could afford to send her to Sydney to learn shorthand and typing”.13 She also recalled that “at the place she attended they gave her an extra free lesson after lunch because she had to travel so far [from Riverstone to the City].”

Clearly, it was of great importance to Mary and Sam that their children should receive a good education and they were prepared to make sacrifices to ensure that this happened. It is tempting to speculate that this ethic resulted both from lessons learned during Mary’s childhood as a schoolmaster’s daughter and from their later life experiences, particularly the hardships that resulted from Sam’s injuries.

The other tragedy that was to be a defining event in Mary’s life was the death of her son, Ambrose, during the First World War. Like so many other young Australian men, Ambrose volunteered for service in the 1st Australian Imperial Force – the AIF. Initially he was posted to Egypt for training before joining the 1st Battalion on the Western Front. Seven months later he was killed during what became known as the First Battle of the Somme.

Ambrose’s body was not found for some time and as a consequence Mary desperately clung to the belief that he had been taken prisoner by the Germans. This belief originated from mistaken evidence given to the Red Cross stating that he had been captured. The uncertainty about what had happened to him seems to have been further exacerbated by what appears to have been at best incompetence or at worst a callous indifference on the part of the military bureaucracy. The Red Cross continued to make enquiries on Mary’s behalf and in August 1917 was able to advise her that it had received unsubstantiated advice that Ambrose’s body had in fact been recovered four months after he had been killed and that he had been buried on the battlefield sometime between February and April 1917. Mary provided this information to the Army’s Base Records Office seeking confirmation. However, this was not received until the publication of the 380th casualty list in January 1918.

Both Mary and Sam died at their home in Crown Road. Sam had been an accomplished cricketer and was at a cricket match being played on the old Nelson cricket ground when he became ill. He never recovered and died about twelve months later on the 5th July 1923. Mary lived for another thirteen years. Her death, in 1936, was reported as “somewhat sudden, and was quite unexpected by those near and dear to her.” 14 Both Mary and Sam are buried in Riverstone cemetery.

MARY’S SAMPLER

In 1972 ownership of the family home passed to Cass Mason and in 1976 following the death of her brother, Vincent, she decided that the time had come for the property to be sold. Vincent had been the last member of the family to occupy the Crown Road house.

This decision inevitability meant that the contents of the house – the accumulated family possession, papers, photographs and memorabilia had to be disposed of. This included Mary’s sampler which had remained a cherished family keepsake for just over a hundred years.

Knowing of Laurie Hession’s interest in conserving the past, Cass entrusted the sampler and a number of other items to him for safe keeping and now Laurie’s family have in turn passed the sampler on to the Riverstone Museum for its safe keeping.

-

- Jan Burnswoods & Jim Fletcher, “Sydney and the Bush – A Pictorial History of Education in NSW”, NSW Department of Education, Sydney 1980, p57.

- Ibid, p65.

- NSW Powerhouse Museum, “Statement of Significance – Embroidered Sampler by Eleanor Anderson, 1900”, WWW.powerhousemuseum.com.collection/database/.

- NSW AO, Miscellaneous Letters ‑ Denominational School Board (185255), Minutes dated 7th December 1853 from Archdeacon McEncroe, 1/313.

- NSW AO, Denominational School Board, Miscellaneous Correspondence, Application to establish a Denominational School at Nelson, 14 December, 1866.

- NSW AO, Miscellaneous Letters ‑ Denominational School Board (185255), Minutes dated 7th December 1853 from Archdeacon McEncroe, 1/313.

- op. cit

- The Catholic Press, 8th August 1935, p27.

- NSW AO, Nelson School File, 5/17086.1.

- Windsor & Richmond Gazette, 16th February 1901, p12.

- Windsor & Richmond Gazette, 2nd March 1901, p3.

- Cass Mason, Riverstone, 11th July 1982, conversation with the author.

- Cass Mason, Riverstone, 11th July 1982, conversation with the author.

- Windsor & Richmond Gazette, 6th November 1936, p3.