by Shirley Seale

The Hawkesbury River has flooded, I imagine, since the beginning of time. The first recorded flood took place in March of 1799, and it was a big one! Already the area was being used to grow a food supply for the settlers and convicts in Sydney, so devastation of the crop lands was disastrous and nearly resulted in starvation for all. There was another flood in 1800, then 1806 saw three floods in March, June and November, when 38,000 pounds (millions of dollars in today’s money) worth of property was destroyed.

Governor Bligh became a well-loved figure in the region by introducing Government relief to the farmers who had lost everything. Another big flood in August 1809, resulted in Governor Macquarie establishing the five Macquarie towns of Windsor, Richmond, Castlereagh, Wilberforce and Pitt Town and encouraging farmers to secure a block of land on these high grounds to which all harvested produce could be removed to safety.

Many of the new residents of the Riverstone area have never stood at the railway crossing at Garfield Road seeing only the roofs of the houses across the line visible above the flood waters. The last time we were cut off by road from the surrounding areas was in February of 1992, but the older Riverstonians have their own memories of the wreckage and trouble they caused. My own first experience came one month after we bought our house here. Having grown up in Newcastle I was unaware of the flood dangers at Riverstone, but witnessed the huge flood in November 1961. Through sheer luck, not knowledge, our house was on the high side of the railway line.

Reading through the back copies of the Windsor Richmond Gazette has shown many facets of the trauma and distress caused by our antecedents at Riverstone during the floods of many years.

The following accounts will let you feel the terror and dismay of the people in our community at these times. As there have been 120 floods recorded on the Hawkesbury, I will only give the details of some of the biggest, and how they affected the Riverstone area.

On Tuesday, 27th July 1857, the flood closed the road at McGraths Hill and people were ferried over by fragile boats above the house tops. By Wednesday, 28th, water had risen another six feet,(almost two metres) during the night. Tebbutt’s House at McGraths Hill became an island in the highest flood since 1817. This time the flood was not caused so much by rain as by the heavy snow fall in the mountains melting and the water rushing down. There was no loss of life, but the editorial stated, “we shall find the damage and impoverishment will in some measure attack a very large portion of the people”.

Then, on the 24th August of the same year, “Woe upon woe! Another inundation has visited our unhappy district.” The second flood rose more than two metres higher than the previous one in July, and covered all the surrounding areas. However the ship the “Dunbar” had been wrecked at the gap only a few days before and the news of that tragedy, with the stories of the two survivors and the horror of the loss of life kept the Windsor flood off the front page.

In February 1860 the bridge at North Richmond was covered, but the flood subsided quickly, only to be followed by another in April when McGraths Hill was covered and no mail could get through. When a third occurred in July of the same year the paper said there was no point in starting a relief fund as people had no more money to give and when in November a flood hit as the harvest was underway, many farmers were forced to give up.

There were widespread floods throughout the state in 1864, when every river from the Fitzroy to the Moruya had flooded and the water at Windsor was hailed as the worst flood it had known. The toll house was carried away and there were only four houses left clear between Windsor and Pitt Town the rest being covered in “unctuous mud”. A Captain Saxby propounded the theory that the moon was responsible for all the bad weather because every time the moon passed over the equator the weather was disturbed. The Sydney Morning Herald printed pages on this theory and its rebuttals because every one was so concerned about the changes in the weather. (Reminds you a little of the global warming debate we are immersed in today!)

The first time the name Riverstone appeared in the paper connected to flood damage was in the truly horrendous deluge which began on 22nd June 1867, which reached the record height of 19.26 metres at Windsor Bridge. The first intimation of trouble to those outside the area was a terse message from William Walker, Windsor Parliamentarian, to the Colonial Secretary: “Send boats to Windsor by train, then water. Fear loss of life”. From the Minister for Works, Mr Byrnes, to the Colonial Secretary: “I have sent four boats to Windsor. Got to Riverstone in time with boats to save family on roof of house”. In fact it was two families, one consisted of seven people and the other was a widow and three or four children. So much water had surged down the rivers and creeks that a boat could be taken from Riverstone in deep water to the Blue Mountains, said the paper. Before long the railway lines were submerged and the railway engine could not approach within half a mile of Riverstone station.

At Riverstone, only two houses escaped the flood and they were only a few feet from the edge of the water. The ridgepoles of the station houses at Riverstone and Windsor were showing only two feet above the surface of the water. There was a fierce gale. The telegraph lines were not working so getting messages for help and information was not possible. How easy it is to forget the difficulties of communication experienced in the mid- nineteenth century, in these days of mobile phones!

But if Riverstone was in peril, Windsor was much worse off as the two mothers and 10 children of the Eather family, who had climbed on to the roof of their house for safety as the water rose within, were swept away and all drowned. (To read more of the 1867 floods in Windsor, see Michelle Nichols’ book, “A disastrous Decade.”)

A train ran between Parramatta and Riverstone, bringing rations, a ton of flour and bread. In true Victorian fashion, the newspaper ran a quote from Shakespeare’s “King Lear”:

“Poor naked wretches whereso’er you are

Thou bide the course of this pitiless storm

How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides

Your looped and windowed raggedness defend you

From seasons such as these.”

There was fear that the railway line to Windsor would not be able to be re-opened when the water began to recede, because “the ballast was of inferior description and now has the consistency of mud”, but the line to Mulgrave was clear by 26th June. A relief fund was begun and quickly raised enough for distributions by local committee. Ideas were put forward that a channel should be cut from Richmond to Wilberforce as the curves in the river were thought to produce the bad floods, and to bring in Government regulations to force people to build above flood level.

There had been eight more large inundations between then and 1879. In her book, “Rouse Hill and The Rouses”, Caroline Thornton quotes from a letter that Bessie Buchanan Rouse wrote to her mother on 10th September 1879:

“The road to Riverstone is quite impassable. One of the bridges is washed away and the water is high across the road. Ashton tried to get over this morning but had to turn back. Whitling (their coachman), managed to ride through the bush at the back with this telegram and even there he says in some places the water was up to the girths – it looks a perfect sea all in the flats between here and Box Hill down by the creek”. That time and there were two floods in the month, the water was 13.19 metres over Windsor Bridge.

It was only the next year, when a great flood started on Friday, 26th May 1889 after three days of solid rain. By Monday, with many houses and shops flooded people began to be alarmed. They tried to get news but the telegraph line between Riverstone and Parramatta was broken, and also the southern line. During the afternoon word came that several families at Riverstone were in need of assistance and had no boat. One was sent by train on Monday, but it overturned by 8 am and one of the occupants, a man named Jenkins was missing, the others had perched themselves in a tree. The Brigades’ boats were not watertight and it was dangerous to use them at night. 12 inches (30 centimetres) of rain fell in 24 hours.

1890 was another bad year with three floods. On 1st March the flood water at Eastern Creek rose level with the floor of the bridge which leads to Blacktown Road. All low-lying land around Mr Joseph Craig’s wool washing establishment was covered with water, and the rain did great damage to the grapes, which were growing in the area. It happened again on 15th March, exceeding the last.

60 centimetres more would have put it in the Neverfail Hotel. Mr Craig and Mr Court were flooded out, and traffic around Marsden Park was blocked, as the water was about 8 feet deep (2 ½ metres) over the bridge.

On March 29th, the Gazette reported a Drowning Accident at Riverstone.

“Rain commenced to fall steadily on Sunday morning and on Sunday night, Monday and Monday night it came down in torrents….. Mr Edward Simpson, contracting for the mail between here and Rouse Hill and who lives on the Marsden Park Estate, at about 5.30 pm, in attempting to cross the creek from Marsden Park, was drowned…..Mr Joseph Court, who saw what had happened ran with a pair of spring cart reins and met the deceased at a bend in the creek. Mr Court succeeded in drawing the reins around the deceased… but he did not make an attempt to grab them. It is thought he was almost gone at that point. This was the last that was seen of the unfortunate man. His wife tried to prevent him crossing, but being of a determined disposition, he would continue it.”

Mr Noble Hanna heard the screams of the bystanders and jumped into the creek, but could not find him and had to be taken to Mr Woods’ home to get dry clothes. Mr James Dick of Windsor lent a boat on the Tuesday morning and the horse and vehicle, with broken shafts, were found, but no trace of Mr Simpson. “The deceased was a fine old fellow, and was never known to do anyone an injury. He leaves a wife and child.”

The paper called for the Government to provide a boat for the future.

July of 1900 saw the next really big flood appear – measured at 14.08 metres at Windsor Bridge.

On 7th July, Riverstone reported the water higher than it had been in ten years and it was in imminent peril. On 14th the paper stated: “Marsden Park has been quite flooded out. Mr W. Davis has lost his all. His house and furniture are partially destroyed and he is staying with his brother. Mr A. Pierce had to leave all and clear for life from the rising flood with his family. Mrs Wilson lost very severely and it is feared her house will fall. Mr Holding lost 17,000 bricks. This is a severe blow to him. Mr Pomfret lost a new piano besides all furniture and effects. Mr McPhee in his home- made canoe did good service to the people of Marsden Park. He paddled to Riverstone and brought back letters and papers. His canoe was made out of a single sheet of 8 feet, (2 ½ metres), of galvanized iron…… Every youngster will be trying to make one”.

By the Thursday night water had entered many of the houses along the railway line and residents were moving out their furniture and belongings as quickly as possible. At the meatworks, water had submerged the offices and other buildings, got into the engine shed and damaged the electric plant. A number of pigs were drowned. The Gazette carried the following report:

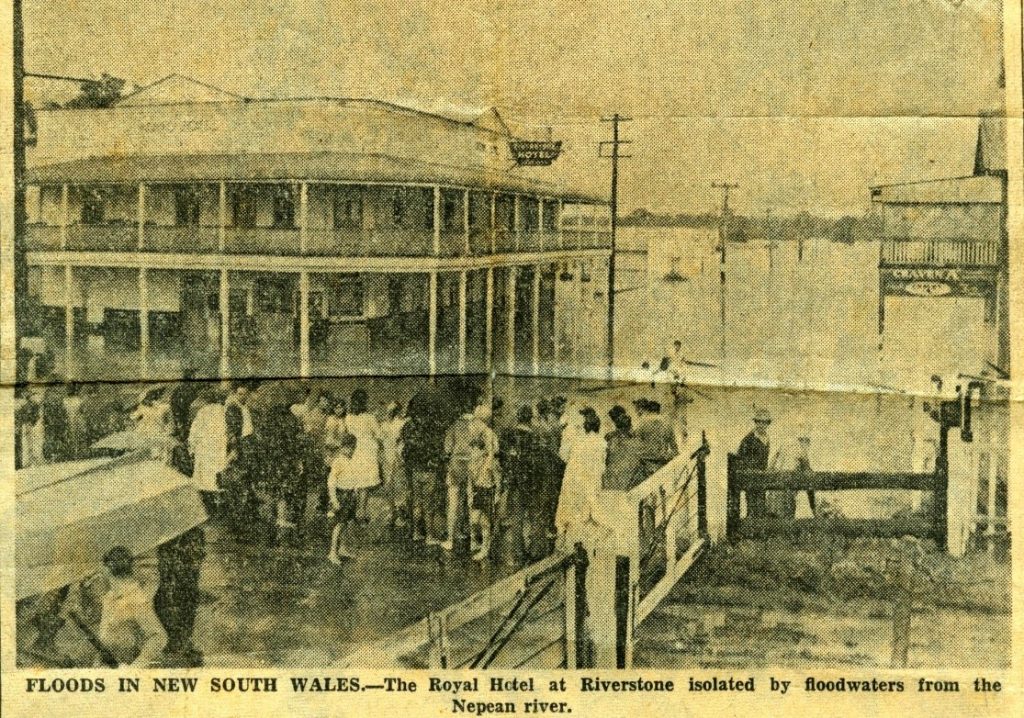

“In Mr Wonson’s Royal Hotel, a two storeyed building, the water reached as high as the ceiling of the first floor. Mr and Mrs Wonson and the other occupants remained on the top floor, but were prepared to leave at a moment’s notice. Fortunately there was no lack of willing hands to offer assistance or many lives would have been lost. Constable Grigor is to be recommended for the way he worked. He and a party were out Thursday and Friday nights saving much property and lives. “

Butchers from the meatworks, J. Aird, R. Wheeler, Sheffield and W. Miles came in the 10.23 train to Windsor, the last one to get across, where they found a boat to use and were able to rescue Mr E. Stokes, and Mr J.Montgomery and his family. Listed among the many who were washed out by the flood and lost a lot of property were Mr P. Quinn, manager of the meatworks, Mr E. Bradley, accountant, and Messers J. Edwards, C. Robbins, N. Morrissey, J. Brown, W. McCarthy, J. Cobcroft, G. Smith, B. Hodgson, T. Davis, E. Stokes, W. Davis, J. Commerford, A. Drake, J. Mason, D. Cummings, H. Cragg, J. Pomfret, J. Montgomery, A. Pierce, F. Carey, H. J. Williams, C. Mortley and many others.

The flood waters which had seemed to ease on the Thursday had crept up silently during the night and people woke on Friday morning to find their homes completely surrounded by water. Trains could only come from the city as far as Riverstone as the viaducts were covered in water and the patrons who wanted to go by boat from here to Windsor and Richmond were advised against it by the Station Master, Mr W. Allen. He had been informed that the current and surf made it positively dangerous as well as the trees and debris and other dangerous obstacles. Mr Joseph of the Riverstone Hotel, Dr Studdy and others threw open their doors and provided shelter.

A man was reported on the roof of the little chapel at Clydesdale on Richmond Road, but when a boat got there only a hat and coat were on the roof. On the Monday the body of a tramp was discovered floating, by Harry Woods’ son, (of Clydesdale). He was about 50 and as he had a tattoo of an anchor on his arm, he was believed to have been a sailor.

Traffic to Marsden Park was restored by Monday and the Gazette wrote that Miss Pitt, a teacher at Marsden Park, who came down from Windsor at 7.30 am was, they thought, a little disappointed that she could resume her duties again! The houses were left so damp that it was agreed it would probably be six months before they could be lived in again safely and much sickness was anticipated because of the damp. On a lighter note, two cats which had floated away on a plank found their way back to the Jordan Mills wool scouring works. A total of 27 houses on the south side of the line were flooded.

The floods came irregularly, but inevitably. Sometimes six or more years would elapse between them. There were none between 1916 and 1922, or from 1925 to 1934 and not again till 1942, but the rivers broke their banks eight times in 1950, three times in 1951, four times in 1952 and seven times in 1956.

The flood in February 1956 was said to be the biggest in 55 years. There were actually two lots of flooding within a week. There were 20 homes affected in Riverstone and the occupants were taken in by others in the community, who also helped to clean out the mud and slime which was left behind after the waters subsided. There was a third flood a week later, but not so big, and the Red Cross Depot in Windsor helped to provide necessary items for the families.

The completion of the Warragamba Dam followed by five flood free years, had led people to believe that the Hawkesbury had at last been tamed, but in November 1961, the worst flood since 1867 occurred and submerged houses in Windsor which had been flood free for almost 100 years. South Creek and its tributaries, Eastern Creek and Killarney Creek overflowed and covered much of Riverstone and Vineyard.

The water started to rise on 19th November, and the flood -gates at Warragamba Dam were opened at 3 am sending massive waves of water down the river. Unfortunately, logs and debris raging down the river stopped the gates being closed again. The western side of the railway line at Riverstone was inundated and 300 people were evacuated from 90 homes. Volunteers worked for two days helping to move possessions out of the encroaching flood waters. The Prime Minister, Sir Robert Menzies, promised to work with the NSW Government to assist in relief funds.

The Riverstone Meatworks were completely flooded, (to read more about this see “The Riverstone Meatworks” by Rosemary Phillis) and the homes that were damaged were in Richards Avenue, Garfield, Litton, Delaware, Burfitt and Carnarvon Roads and Creek, Denmark and Carlton Streets.

It had been the wettest November since records began in 1881, with 1748 points of rain. The State Governor, Sir Eric Woodward travelled to the district and emergency distributions of clothing and necessities was arranged. Although it had been said in 1956 that we would never see a bad flood again, now the Water Board stated that the flood would have been much worse without Warragamba Dam.

As the flood subsided, Windsor Council undertook to investigate a high level road from College Street in Richmond to Blacktown Road to give flood free access. It only took another 40 plus years for a smaller flood free access road to be built!

Column from Windsor & Richmond Gazette, 29th November 1961.

On Being Flooded Out.

How would you react if a group of men came to your house at 11 o’clock at night and told you to start moving out immediately? Something like this happened in more than 100 homes last weekend.

For some indefinable reason, just about everyone in the path of rising flood waters harbours the hope that it will stop just before it enters their particular home. This kind of thinking does not help the rescuers or the householders in the long run. But everyone understands it is not easy to empty your home in an hour.

Things start to happen. Out goes the piano first. Pianos fall apart even after the shortest immersion. Then the refrigerator and other heavy furniture. An anguished cry from the bedroom has nothing to do with the housewife breaking down because her possessions are going. She has noticed fluff under the bed!

A call goes out for someone with electrical knowledge to disconnect the stove. This is a signal for another agonized yelp from the housewife as a small patch of grease appears where the stove has stood for the past five years.

Time is running out. Doors are being taken off their hinges, cupboards emptied out until all the precious suitcases, boxes and cartons are overflowing. All the rest must now be packed onto higher shelves. The kitchen is raided for unopened cans of fruit to put under table legs and other places that cannot be moved. Doors are placed over the shower recess and piled high with knick knacks.

While all this is going on, the children are kept in bed and asleep if you’re lucky. The budgies get VIP treatment but the cat is a problem. He’s prepared to stick to home until it founders. The family dog knew before you did that something terrible was about to happen, so that’s why he just got out of the way and watched disconsolately.

At last everyone is satisfied that all the remaining chattels are at least three feet high and the flood is not likely to rise more than a foot if it does come into the house at all. But it does, and that’s another story.

With every group of rescuers there’s always a leader. Nobody appoints him and he doesn’t even know himself that he’s the leader. Luckily in such crises, those few odd bods who harbour delusions of grandeur and other psychotic problems are safe and warm. After the event they are ready and willing to tell everyone what they should have done.

This was a light hearted look at the problems facing the evacuees, but the really horrible part comes when they return. For floodwater does not leave a home sparkling clean. It leaves behind mud and sludge and debris. The walls have to be removed as Gyprock can’t withstand water, and the smell that the muddy water leaves behind is literally breath taking. Many volunteers are at hand to help with this heartbreaking task after all the floods. We live in a very caring community and we look after each other.

In May 1962 there was a heavy downpour which did not rate as a flood for recording purposes, as it only caused local roads to become impassable. However it had tragic results. On Saturday evening, 13th May, Mr Alan Coles was driving his wife, Edna, their daughter Ann and two young friends, Lynette Hardinge and Laurel Elith home to Schofields from Katoomba. When they reached Grange Avenue, they were unaware that the causeway was flooded and that the water was flowing strongly. The car and all its occupants was washed away and was not found until the next morning, 180 metres downstream, with all occupants deceased. The whole area mobilized to raise funds to help the three Coles boys, all under twenty, to keep together and manage the family farm.

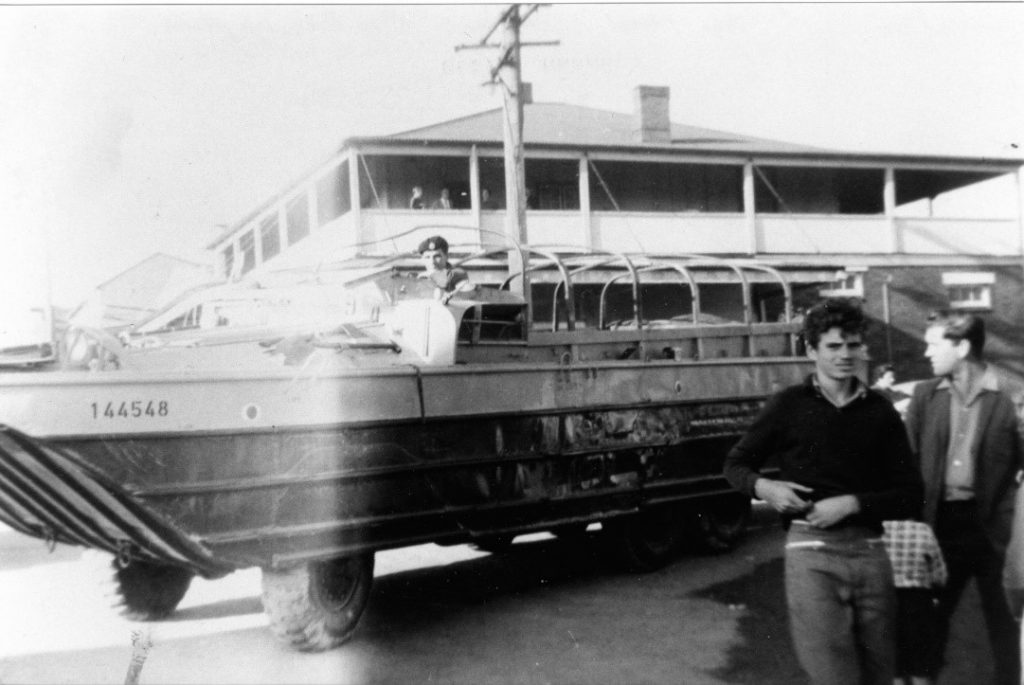

There were four small floods in 1963, but in June, 1964, 100 homes in Riverstone were again damaged on the south side of the railway line when the creeks overflowed once more. Sergeant Paine from Riverstone police was in charge of the local rescue efforts, and two amphibious army “Ducks” were sent from Richmond where they were assisting the Civil Defence force in the rescue, bringing food and fodder and transporting workers to restart essential services.

Water Police and their boats were also used to cope with the strong currents. 86 train passengers, including some schoolchildren, who had been stopped at Mulgrave Station and sent back to Riverstone, were accommodated in the Primary and High Schools here and meals were provided to them by volunteers.(Unfortunately there are always a few who try to benefit from others’ disasters and later some local lads were charged with stealing cartons of beer while helping to remove stock from the cellar of the hotel.) It was a long time before evacuees from the Pitt Town area were able to return to their homes, I remember, as I was teaching at Windsor Primary School at the time and we had families billeted in our assembly hall for many days.

Photo: Bromby family.

The water being released from Warragamba Dam was seen to be a big problem and Councillors from all local councils involved formed a Hawkesbury Flood Mitigation Committee to see if an authority other than the Water Board could have control of deciding when the water gates should be opened at flood times. This came to nothing, and as this was the year the Beatles visited Australia, the flood water debate was soon pushed from the front pages.

In the next 14 years, there were 14 floods of varying ferocity in the area, including six in 1974, but the next really serious one came in June 1978. It began on Tuesday, 21st March, and all the gates at Warragamba Dam were opened, releasing 520,000 mega litres of water downstream every 24 hours, the equivalent of a day’s usage for Sydney.

The dam had been 4.16 metres below full when the heavy rain began. Once again Riverstone lowlands were covered and the long-suffering residents were once again evacuated with as much of their belongings as could be rescued. Once again our township was isolated with the roads leading in all directions covered in impassable sheets of water. A Flood Relief Office was set up by the Department of Youth and Community Services, in Market Town shopping center, to help those in need.

1988 saw the Bicentenary and the opening of our Museum at Riverstone, but also saw another two floods in April and July. The April one I remember, as my father was in Windsor hospital. My sister brought Mum down from the mountains, but we couldn’t drive up as the roads were covered and had to go and bring her back in the train. It was her first sight of the expanse of water that covered this area at such times.

In August 1990 we had the biggest flood in 12 years. As the water came down from Warragamba dam the river had waves a metre high, but the Water Board insisted that the flood waters would have been two metres higher without Warragamba Dam there. We all suffered the same fate once more with the roads cut, and the residents across the railway line trying to protect their property. Once more the councils called for a flood free evacuation route to be built.

The last flood to come to our district was in February 1992. This one was measured at 11 metres at Windsor Bridge and was not as severe as many we have lived through, although once again, it was not possible to drive out of Riverstone as the roads to Marsden Park, Windsor, Parramatta and Penrith were cut for some time, and looking across from the railway station you could see nothing but a large expanse of water.

As you drive through Richmond and Windsor, there are still occasional signs showing the depth of the water in previous floods. If you have never seen it, it is hard to imagine the water so deep that people are being taken off by boat from the top floor of the “Jolly Frog Hotel” at McGraths Hill, but we old time residents have seen it happen.

The Penrith Lake Scheme is supposed to be the answer to the easing of floods in the Hawkesbury Valley, as the excess water run off is to be trapped in the man-made excavations and so prevented from coming downstream to us as it has done in the past. At least now, our flood free access road from Windsor is a reality. Maybe our flood history will end in February 1992, but only time will tell.