Compiled from a presentation by Shirley Seale

at Rouse Hill House on ANZAC Day 2007

When World War 1 was declared in August 1914, Australia was a small country of only five million people, but we were fiercely loyal to the King, George V and the British Empire. Our Labor Prime Minister Andrew Fisher stated firmly, “We will defend the Mother Country to the last man and the last shilling”. He made an offer of 20,000 men for the Australian Imperial Force and by 20 August, 10,000 men had enlisted in Sydney alone.

These were the men, but what about the women? Women were still pretty much under the control of their husbands, fathers or brothers. They were confined, not only by social custom to be content with “a women’s place in the world”, but even by their clothing. They were restricted by the corsets they were expected to wear to produce a fashionable shape.

Only 24% of women were in the workforce at the time that war broke out. These were mostly women in low paid jobs like shop assistants, some clerical workers, some teachers and nurses, but largely domestic workers or servants to the more affluent.

The women were patriotic too and wanted to be involved in this war effort. They tried to enrol in the forces, but were refused, they offered to take the men’s places when they went to fight but were refused. They tried to be ambulance drivers, but although women were welcomed in other countries in this role, in Australia they were refused. Dr Agnes Cooper, a medical practitioner with 25 years experience was told by the recruiting officer if she really wanted to help the war effort she would go home and knit socks. (She actually travelled overseas to enlist and had a distinguished record.)

Lots of support was needed by the troops. For every soldier who went to war, it was estimated that another forty people were needed to support him – doctors, nurses, ambulance drivers, sailors, truck drivers and factory workers. Going to war meant that the whole of Australia had to join in the work.

Mothers and children had to do without the men’s wages, although a portion of the soldier’s daily pay could be allocated to those at home. Many women took in boarders, did other people’s washing and housework. Children left school as early as possible to help support the family.

Some of the changes made to everyone’s life by the War Precautions Act, included the imposition of income tax by the Federal Government. This had only been done by State governments previously, so now there were two taxes to pay. The Federal Government could now raise loans to pay for the war, fix prices, intern people with backgrounds from enemy countries, compulsorily purchase farmer’s crops and censor mail.

Toy manufacture for children was severely curtailed and children began to make their own toy guns to play-act battle scenes, and girls dressed up as nurses. Children were flying small copies of the Union Jack flag on their scooters and bikes and the books published for them often included war themes. Writers such as Mary Grant Bruce and Ethel Turner, amongst others, had their characters enlist in the army.

So what did women do? Their attempts to play a constructive role in the war effort were never taken seriously, so for most, voluntary work was the only option available and they took to it with zeal and energy.

Voluntary Organisations

Women were told that the greatest sacrifice they could make was giving their sons, husbands, fathers and brothers to the slaughter, and they were expected to contribute only in appropriate ways. Knitting socks was appropriate, using a rifle was not. Approximately 10,000 patriotic clubs were formed during the war to provide comforts for the troops.

The Red Cross

In New South Wales 88 city and suburban branches and 249 country branches of the Red Cross were formed. In their first year of activity they sent a total of 605,370 items of comfort to the troops, made up of things like hats, toothbrushes, pyjamas, towels, underclothes, handkerchiefs and socks, with a total value of £93,781. With the basic wage of the time a little over £2 a week for a family of four, this was an incredible effort.

Riverstone formed a branch in September 1914, with Mrs Anstey, the headmaster’s wife as president. Mr Cohen, a local storekeeper, donated a roll of flannelette for them to make pyjamas for the wounded soldiers.

On 15 August, a group of ladies met to start the Kellyville-Rouse Hill branch of the Red Cross. The president was Nina Terry, secretary Miss Redden and treasurer Miss M. Pearce. At the October meeting they brought items such as six pots of marmalade, a fowl, six dozen eggs and two beautifully worked camisoles. These were sold to other members and the money used to buy comforts for the troops. They were already sending them soldiers bags, twenty five cholera belts and six Balaclava hats. (Cholera belts were made of flannel and were designed to be wrapped around the stomach to ward off gastric complaints.) Sewing bees were held in the school room at Rouse Hill house. A pattern used for crocheting mittens is still amongst the possessions at the house.

One of the special tributes that Nina Rouse paid to the soldiers was to use leaves from the loquat tree in the garden at Rouse Hill House, every ANZAC Day to make a wreath to hang on the gate of the little Christ Church on Windsor Road at Rouse Hill. It is a tradition that is continued by the staff and volunteers at Rouse Hill house, though these days the wreath is hung on the door of the church as the gate has gone.

Donations to the Cause

It was necessary for the women to work at providing supplies, as the troops were very poorly equipped for the kind of territory they were fighting in. They were encountering freezing conditions in France and had insufficient warm clothing, so sheepskin vests were added to the items being sent from this area. In Windsor, three small girls, Thelma Fewings, Marjorie Mitchell and Madge Williams, held a children’s fete and gave 14 shillings to buy two sheepskin vests for the soldiers.

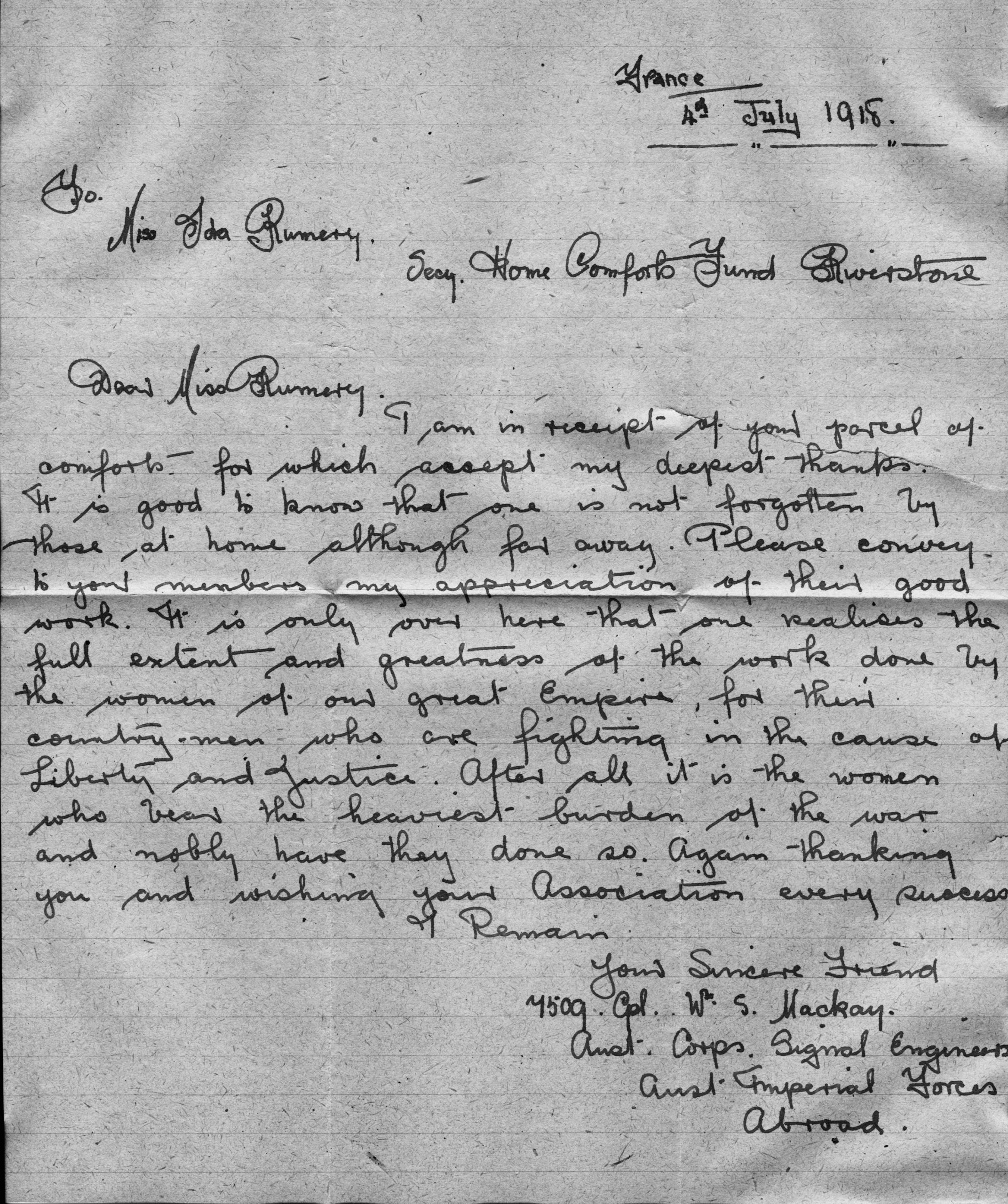

By 1916 Kellyville-Rouse Hill branch had sent away 401 items and donated over £186 pounds. Riverstone branch, under the presidency of Mrs Anstey, then Mrs Cruickshank, secretary Mrs Vidler and treasurers Emma Rumery and A. Fletcher, had in the same time sent 366 items and raised £228. They had sent 24 Christmas packages and remembered Randwick Military Hospital with a gift of sweets for the wounded.

Conditions in the Trenches

The women knew that the men in the trenches were having an uncomfortable time. The food was very poor and there were rats, lice and fleas. The soldiers always asked their families to send flea powder and lice powder. They just had to learn to live with the rats, but sometimes they ate them if the food was scarce.

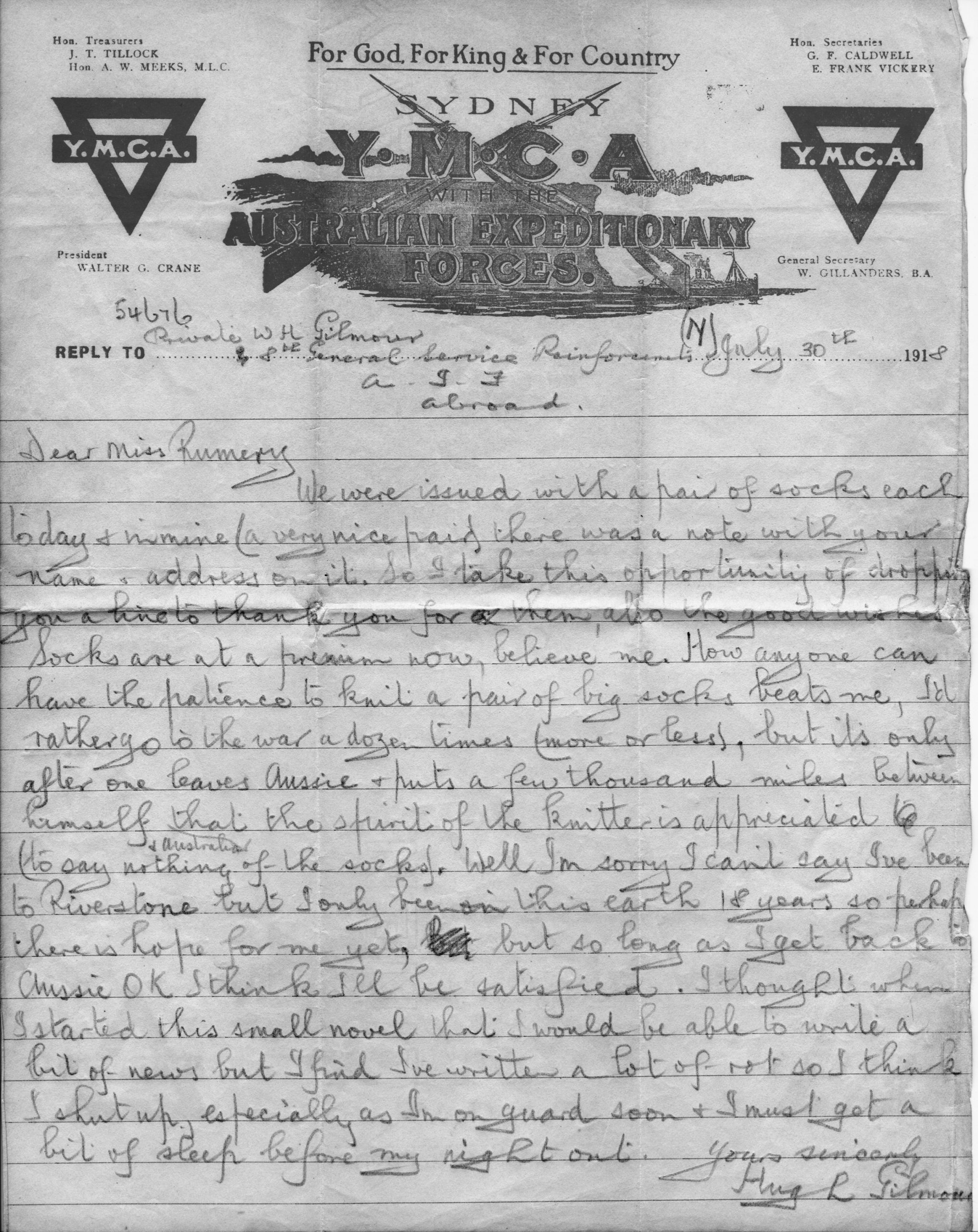

Their feet were often wet from the water collected at the bottom of the trench, causing many to develop “trench foot” and having to be taken out for treatment. The women knitted socks for them to keep their feet dry, as each soldier was only issued with three pairs.

The Socks

Knitting socks for the boys was an important part of the women’s and girl’s lives. Rosemary Phillis of Riverstone says her grandmother, Ida Rumery, recalled knitting socks for the Home Comforts Fund. The women knitted whenever they had a spare moment, even when they were walking around the house. Knitting the leg and foot was no problem, but the heel was difficult because of the shaping. Difficult of not, they kept knitting. When steel for knitting needles was no longer available, they used the sharpened spokes of bicycle wheels to knit the socks with. My aunt Muriel did that. Altogether the women of Australia sent more than one million pairs of socks to the soldiers. Not a bad effort when our total population was only five million people. One frustrated woman wrote to the newspaper in 1916 saying, “hundreds of intelligent women are wondering whether they may not be doing something more helpful than knitting and making flannel garments”.

In the last year of the war Kellyville had maintained their output. The Red Cross groups raised money in many ways with euchre parties, musical evenings and Riverstone even held a remarkable cricket match in which the ladies team played against the men, who were suitably handicapped by batting with their opposite hands and using stumps and pick axe handles as bats.

In April 1917, a sports day was held at Mr George Terry’s old racecourse at Box Hill in aid of the Kellyville-Rouse Hill Red Cross. People came in cars, motorbikes, drays, buggies, sulkies, perambulators, while a number came on “shanks pony” (walking). The admission charge was one shilling for adults, and two pence for children. Over £21 was raised.

The Patriotic Fund

The Patriotic Fund had been formed by the Lord Mayor of Sydney who issued a directive to local councils to form a branch in their municipality. In Windsor a meeting was held. The appeal for funds was to be voluntary, but it was decided that if someone gave money after answering a knock at the door, it should be considered as voluntary. The names of those people donating were printed in the local press. Both in Windsor and at a subsequent meeting at Riverstone, £50 was donated to get the appeal going. The employees of the Riverstone Meatworks held a fancy dress ball. By the end of the first year, £19,787 had been raised in Sydney. 6,000 carcases of mutton, 6000 tins of jam and 100 cases of preserved meat had been sent overseas. Throughout the war these funds continued to grow and citizens felt they were doing their best for the boys at the front.

These circles of women, working enthusiastically for the common cause of aid to their fighting men became a strong support for each other, in worrying, anxious and sad times. They became quite powerful political lobbies at times like the conscription referendum.

Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD)

The VAD was formed to assist the Australian Army Medical Corps. They were unpaid and had to provide their own uniform. They cared for the wounded soldiers coming home, met troopships at the docks with food and clothing for the men. Sometimes as many as 1,400 wounded men were disembarked. The VADs acted as assistant nurses and generally came from well-to-do families.

Kathleen Rouse sailed for England just two weeks after the death in battle of her fiancée, Captain Norman Pearce. There she stayed with an aunt and joined the VADs. She wrote a poignant letter home telling of the terrible sights she was witnessing. These young women from privileged backgrounds were seeing the horror of war at close quarters.

The Nurses

Trained nurses in Australia in the early 1900s were generally from what we would call “middle class”, as they had to be supported during their three year training by their family, as well as being equipped with uniforms. The normal working class family could not afford to do this.

During World War I about 3,000 Australian nurses served overseas as part of the Australian Army Nursing Service. Nurses from the Hawkesbury district who served included: Nurse Hendren, Sister Dickson, Sister Louise Young, Nurse Vida Greentree, Matron Alice Mary Cooper and Matron Julia Bligh Johnson.

Send Offs

When the soldiers left the district to begin their service, the women gave each soldier a great farewell party, with singing, dancing and speeches from local dignitaries. They presented them with farewell gifts:- shaving equipment, pens, tobacco pouches and often a wrist watch, a very expensive item at the time, with a reminder that “every time the soldier looked at the face of the watch, he should remember the faces of those at home who wished him well”. The local papers at the time declared that the halls on these occasions were decorated beautifully, as usual, by “the fair sex”.

At Riverstone, Miss Matilda McCabe, a teacher at the local school, had become a driving force behind all these activities. She had organised a First Aid Class and her girls, dressed in white with a red cross on their aprons, took part in all the activities. She announced that she was going to war as a nurse, and a grand community farewell was held for her. Then her plans fell through when her mother, who was very ill, made a dying wish that Matilda should stay home to be there to nurse any of her brothers should they come home wounded from the conflict.

Welcome Home

Having supported the soldiers throughout the war, the Red Cross ladies were there to welcome them home again. The railway stations were decorated with branches and regimental colours and welcome home evenings were organised. Each returned soldier was presented with a gold medal, and these were pinned on the uniforms by the young ladies. The Windsor and Richmond Gazette reported on one occasion when, “some girls kissed the boys, some boys kissed the girls, kissing was meekly submitted to in most cases, but one or two of the ladies bolted and would not be kissed”.

The Kellyville-Rouse Hill Red Cross held a gypsy tea with games to welcome home some local lads. Mrs Crisp, wife of Constable Crisp of Riverstone was very involved in war work. She was the Secretary of the Patriotic Committee as well as being a member of the Win the War League and the Welcome Home Committee, ably assisted by Mesdames Packer, Brooks, Teale, Wallace, Alderton, Schofields, Voysey and others.

The men from Riverstone gave a wonderful thank you gift to the women who had supported them for the war years. Each lady was presented with a large framed photo board featuring pictures of many of the soldiers with a thank you plaque printed on the bottom. Many of these survive as treasured mementoes through the generations of families since WWI.

The End Comes at Last

Throughout the war years, women were discouraged from showing their grief publicly if they lost a member of the family. They dreaded the sight of the telegram boy, the Postmaster or the local Minister coming down the street in case it was bad news for them, then felt guilty that they had wished the terrible visit on another family instead of their own. They were told that any sacrifice was a noble one, that men died for their country and that the women gave them up “to rest in a foreign field”. By 1916 idealism had waned and they felt they just had to see the ordeal through. Mothers were awarded a medal if they lost a son in battle.

In February 1919, the casualty list for the war was given as 58,037 dead, 166,230 wounded and 82,402 sick. For many young women their chance of marriage had vanished with the death of their sweetheart, and also, many of the young soldiers returned with wives they had married overseas. Many of the young Australian women had been widowed and the community rallied to help the local families left without a father. Riverstone people raised money at many functions to buy land opposite the police station and then to build a home for the young family of Private James Symons who was killed in France on his twenty sixth birthday.

The women did grieve, Elsie Robbins of Riverstone wrote of her brother John Thomas who had been killed in France:-

Somewhere in France my brother lies,

Somewhere in France he fell.

Little I thought when we parted,

It was our last farewell.

In the ANZAC Memorial in Hyde Park, there is a wonderful sculpture called “Sacrifice”. It is a tribute to the mothers, wives, sisters and daughters of the men who fought and recognises the support and suffering that the women endured during the four years of World War I. The women are shown supporting the soldier, lying on his shield and I would like to leave this image in your minds today as we remember not only the heroic deeds for the men, but the strength and sadness of the women of World War I.

As this article came from a speech it has not been referenced. A bibliography is available from the Historical Society upon request.